The Intersection of Liberty and Whisky: What does it all mean, and who cares?

- Nov 5, 2017

- 6 min read

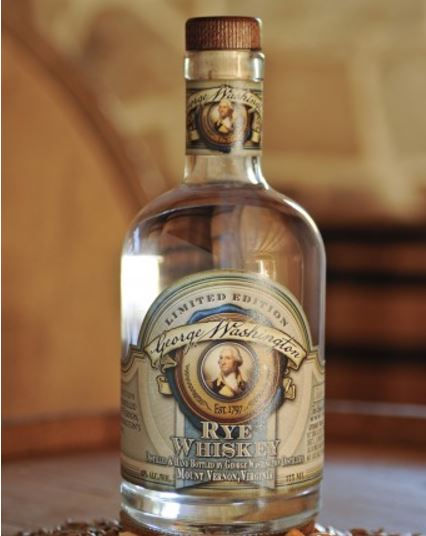

1814, Mount Vernon, Virginia – The structure lay in smoldering ruins. As steam and smoke wafted from the foundation, the only remnants were the chimneys and what used to be five copper pot-stills. Just yesterday, these bad boys were cranking out gallons of sweet, delicious (mostly rye) distillate. In fact, the distillery at Mount Vernon produced close to 11,000 gallons of whiskey in 1799. In double fact, George Washington – the General/President/Supreme Commander/Master of the Constitutional Convention/surveyor of the Virginia border/descendent of Odin/slayer of all his foes – became the largest producer of spirits in these United States. Ironic, considering that Washington, several years before entering the whiskey market, used his considerable power to squash the whiskey rebellion like a chipmunk beneath my Jeep’s tire.

Yes, that happened last week. Yes, I feel bad about it. Go ahead. Shout “Shame” at me.

Questions and considerations

At this point, you’re probably asking yourself several questions. At least, I hope you are.

For instance, what is the significance of George Washington’s legacy as a statesman, and how does that contrast with his role as a private farmer citizen? He was, after all, a man of many talents, and filthy, filthy rich.

You might also be wondering, Can whisky help forge relationships among diverse peoples? Can it help people identify their common goals, even when they advocate for different solutions to common problems?

If Liberty is the soul’s right to breathe (queue the Matt Damon), does whisky open a window to other breathing souls?

And finally, where is the intersection of liberty and whisky, and why should we care?

Seriously. Why. Should. We. Care?

Well…I’m glad you asked (chuckles nervously – cracks knuckles – puts hands in pockets – removes hands from pockets – clears throat – face turns red – stands on one foot – stares at floor).

Keep reading. Please.

Liberty defined

So what is Liberty? Well, if we’re being literal, see below for Webster’s dictionary definition.

liberty

noun | lib·er·ty | \ˈli-bər-tē\

plural – liberties

1: the quality or state of being free:

a: the power to do as one pleases

b: freedom from physical restraint

c: freedom from arbitrary or despotic (see despot 2) control

d: the positive enjoyment of various social, political, or economic rights and privileges

e: the power of choice

The word “liberty” derives from the Latin terms libertas (“freedom”) and liber (“free”). Common, modern derivatives are liberal, which in the classical sense, is closely associated with freedom (more on that in an upcoming blog post), and libertarian, which may produce either a sense of comfort or revulsion, depending on one’s perspective.

Liberty, as described in this article, and as will be used in future posts written by me, can be understood within the context of natural rights, as articulated by Cicero, and later by John Locke, Thomas Paine, and David Hume. It is the right to do as you please, so long as no one else is harmed by your actions. At the risk of being dogmatic, libertarianism (small “l”) is characterized by an adherence to non-aggression, or non-harm, and self-ownership.

In his famous “Democracy in America,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “. . . everyone is the best and sole judge of his own private interest . . . society has no right to control a man's actions unless they are prejudicial to the common weal or unless the common weal demands his help. This doctrine is universally admitted in the United States.”

Representing the Pennsylvania General Assembly (in letter form) in a dispute with the Penn family over taxation, Benjamin Franklin wrote, “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.”

On monarchy, taxation, and the “quintessential American right,” Andrew “The Judge” Napolitano defines liberty as “the right to be left alone.”

The purpose of this blog is to explore what liberty means to different people, and how we can unite by focusing on a common understanding of problems. People who disagree and vehemently argue over solutions can, more often than not, agree on the problem itself. The problem, once clearly defined and quantified, will lend itself to understandable root causes. Once root causes are stated, the prescribed solutions become much, much less contentious.

Thus brings the necessity for reciprocal relationships in government, economics, journalism, etc. By partnering and cooperating, we open ourselves up to additional resources, more perfect information, and moral perspective.

Whisky (uisge beatha) defined

Although distillation likely originated 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, grain-based spirits didn’t hit the scene until much later, approximately 1000 AD. Irish and Scottish monks – legendarily ingenuitive when it came to turning common foodstuffs into alcohol – began fermenting and distilling grain out of necessity. Grapes, the standard base of fermented and distilled beverages of the day, refused to grow in the horrendous island climate.

And thus, whisky was born. They called it Uisge Beatha, a Gaelic term, which translates literally into “water of life.”

In the case of malt whisky, the simple distillate requires only three ingredients - water, barley, and yeast. Place said spirit in an oak barrel and let it set for twenty years – now you’ve got the potential for something really special. Local farmers, having not much else, had those items in abundance. Given the land’s natural resources (i.e. rivers, trees, and fields), various and distinct industries popped up to support the making of whisky. Coopers fashioned wood into barrels; farmers, who already grew barley and other grains, began to supply distillers; brewers and bakers provided the yeast; and distillers combined all these ingredients with the sweet waters of local rivers to make our lovely drams. ☺

Whisk(e)y producers have often found themselves in the crosshairs of state officials and regulators. Whether by taxation of malted grain or the outright prohibition of spirits, countless whisky makers have danced the line of liberty and compliance. All policy decisions have consequences. For instance, 18th century Irish distillers responded to the malt tax by adding unmalted barley to their whiskeys. The practice stuck, and Irish whiskey is still largely comprised of a combination of malted and unmalted grains. Additionally, the prohibition era led to some Scotch whisky producers (i.e. Laphroaig) to sell their product for ‘medicinal purposes only’ in pharmacies. The disastrous effects of alcohol prohibition – which are nearly universally recognized – draw some striking parallels to our current drug war. But I’ll save that for a future post. ;-)

In my 36 years on this Earth, I have found that whisky can act as a remarkable social lubricant, turning uneasy acquaintances or even enemies into fast friends. It eases conversation, promotes truth, and encourages empathy and understanding. The implications of this are profound if A) they are generalizable beyond my own, limited sphere, and B) they can be applied to the previously stated scenarios, in which mutual cooperation and reciprocity is required.

Connecting the dots

So, what do liberty and whisky have to do with one another? And why is George Washington relevant to the discussion? I’ll flip these and answer them in reverse.

First, Washington was arguably the Founding Father. Without him, the American War for Independence from Great Britain may not have been won; the United States Constitution and subsequent Bill of Rights may not have been written, and we may have had kings instead of presidents; the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, and the abolishment of Jim Crow might not have happened without Washington’s role in our founding. It can be argued that all incremental steps and giant leaps towards liberty to have occurred since 1789, have hinged upon George Washington. Though Washington the man was an imperfect standard bearer for liberty for a variety of reasons, he was probably the most important catalyst for our limited, representative, Federalist experiment in governance.

Second, liberty is as important now as it was when Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence and his list of grievances against King George III. We can trace its path through the history of whisky. We see human innovation and the beauty of the free market in whisky production. There is partnership and understanding among diverse peoples. We see cause and effect, and can develop an economic understanding of public policy by observing how whisk(e)y producers have responded to various regulations and impositions. By knowing and recording the effects of alcohol prohibition, we can inform our opinions of other prohibitive laws.

Lastly, in a time of contention and division, whisky can bridge the gaps between vehemently disparate factions. Just as a certain beer producer demonstrated in a recent ad campaign, joint problem solving and conversation over drinks can resolve even the most fundamental disagreements. If you’re seeking to love thy neighbor, offer him a drink.

Post scriptum

In a double-dose of irony, the following note is posted on the current (and fully operational) Mount Vernon whiskey website:

“Note: Virginia ABC regulations do not permit us to ship whiskey or take online orders. Purchases must be made in person with valid government issued ID.”

Comments